The Great Depression: A Monetary Crisis?

In 1929, an event shook almost every country’s economy in the world like an earthquake tearing apart a city. In a matter of days, the wealth of billions vanished as the stock markets crashed, banks failed, and prices skyrocketed. That event, known as the Great Depression, came as the result of a long series of events, and it set the world on the path toward World War Two.

Several theories exist that attempt to explain the causes of the event, with two dominant theories ruling the field of explanations. Experts split fairly evenly between these two primary theories, with some proposing some minor theories that are beyond this assignment’s scope.

The first of these competing hypotheses stems from Keynesian economics. It argues that a drop in the private sector’s demand for goods paired with a decrease in fiscal spending helped cause the economic collapse.

The second, put forward by Monetarist economists, disagrees, claiming a banking crisis stemming from a reduction in money supply stands as the event’s principal cause. It is this cause, primarily put forward by Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz, that this discussion will focus on.

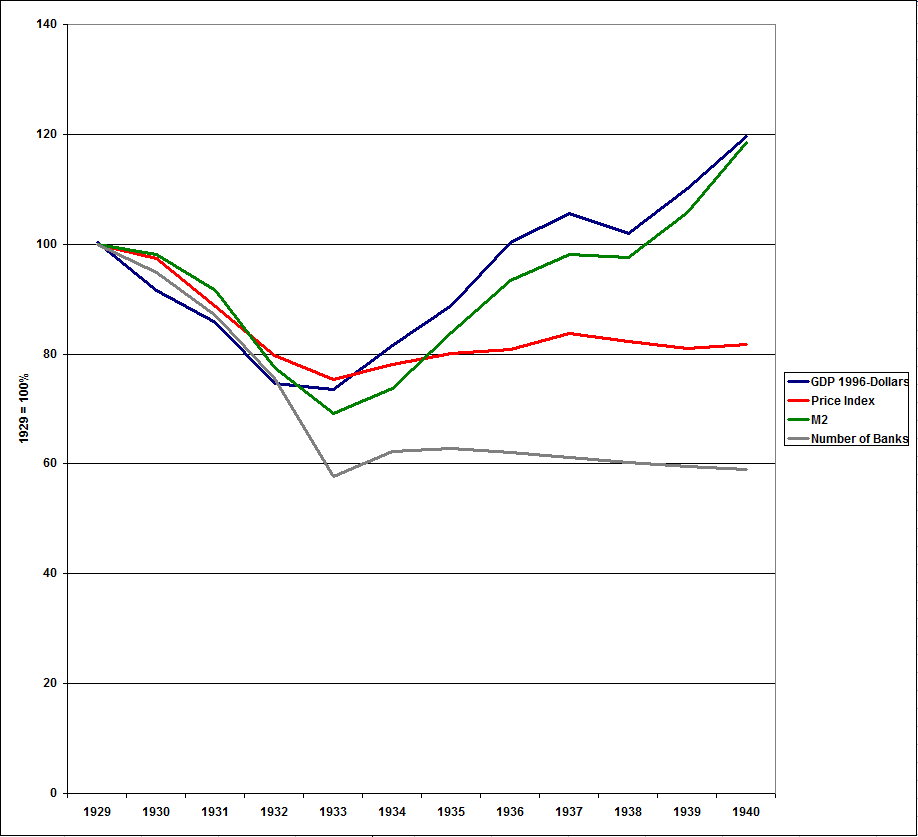

According to the Monetarist argument, a banking crisis started the collapse, leading to a third of all banks closing, a massive loss in shareholder wealth, and a monetary reduction that reached 35%, referred to by Friedman and Schwartz as the “Great Contraction.”[1] These events led to price deflation that collapsed the market.[2]

Friedman and Schwartz, as well as others, argue that a refusal by the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates paired with the government’s unwillingness to boost the monetary base, infusing liquidity to stop a collapse, guaranteed that a simple recession turned into one of the greatest economic collapses in history.[3]

Monetarists believe that, had the Federal Reserve not watched the collapse without taking action, the stock market crash would have led only to a recession as economies see cyclically. The situation called for extreme measures, not quiet observation in hopes it would correct itself. This view regarding the Federal Reserve’s role in the crisis remains strong into the 21st century, with Ben Bernanke, former Federal Reserve governor, publicly apologizing for the inaction in 2002.[4]

Because of their inaction, several large banks collapsed, causing panic and runs on the banks like the one pictured in It’s a Wonderful Life.[5] Monetarists argue that emergency lending at the outset of the collapse may have stopped those banks from going under, heading off the crisis at the pass, to borrow a colloquialism.

After they collapsed, Monetarists point to a lack of liquidity, preventable by the Federal Reserve buying government bonds to increase the money supply, as the cause of the next wave of bank collapses.[6] The lack of money stopped businesses from getting loans or even keeping the ones they already had. This view sets the blame squarely on the Federal Reserve, particularly the New York branch.[7]

When making this argument, Monetarists point to how the Federal Reserve acted in similar banking crises in 1893 and 1907.[8] The Reserve, as well as some private parties, prevented a money shortage from happening by lending money to the banks, thus increasing liquidity.[9]

One reason given for the Federal Reserve’s inaction is the gold standard and the limitations placed on the Reserve by the Federal Reserve Act. It mandated that a minimum of 40% of Federal Reserve Notes had to be backed by gold.[10] The problem with this system was that the notes only amounted to a promise of value, and people, borrowing another colloquialism, now only trusted the one in the hand versus the two in the bush.

With no wiggle room, the Federal Reserve could only cut credit to relieve pressure on the gold supply. It took three more banking crises and a new president for relief of this pressure to come through a New Deal for the nation.[11] By then, the damage had been done, causing a governmental change in Europe that guaranteed a bloody conflict unlike any the world had ever seen.[12]

[1] Milton Friedman, Anna Jacobson Schwartz, and National Bureau of Economic Research. The Great Contraction, 1929-1933. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

[2] Randall E. Parker. Reflections on the Great Depression. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2002, 11-12.

[3] Bernanke, Ben. Essays on the Great Depression. Lieu De Publication Inconnu: New Age Publications, 2007, 7.

[4] “FRB Speech, Bernanke -- on Milton Friedman’s Ninetieth Birthday -- November 8, 2002.” Www.federalreserve.gov, 2002. https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/Speeches/2002/20021108/default.htm; Milton Friedman, Anna Jacobson Schwartz, and National Bureau of Economic Research. The Great Contraction, 1929-1933. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009, 247.

[5] Broff, Ian. “Bank Run Scene from ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ (1946).” YouTube Video. YouTube, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OTJCI1FNBfA; Frank Capra, dir. It’s a Wonderful Life. Film. RKO Radio Pictures, 1946.

[6] Paul Krugman. “Who Was Milton Friedman? - the New York Review of Books.” Web.archive.org. April 10, 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080410200144/https://www.nybooks.com/articles/19857; Bernanke, Ben S. “Non-Monetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, 1983, 257-276. https://www.nber.org/papers/w1054.

[7] G. Edward Griffin. The Creature from Jekyll Island: A Second Look at the Federal Reserve. Internet Archive, 1998, 503. https://archive.org/details/TheCreatureFromJekyllIslandByG.EdwardGriffin.

[8] Milton Friedman, Anna Jacobson Schwartz, and National Bureau of Economic Research. The Great Contraction, 1929-1933. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009, 15.

[9] Randall E. Parker. Reflections on the Great Depression. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2002, 11.

[10] Freidel, Frank Burt, and Internet Archive. Franklin D. Roosevelt : Launching the New Deal. Internet Archive. Boston : Little, Brown, 1973, 320-339. https://archive.org/details/franklindrooseve04fran.

[11] Ibid., 335-339.

[12] Ian Kershaw. Hitler, 1889-1936: Hubris. London: Allen Lane, 2001, 411.

Bibliography

Bernanke, Ben. Essays on the Great Depression. Lieu De Publication Inconnu: New Age Publications, 2007.

Bernanke, Ben S. “Non-Monetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, 1983. https://www.nber.org/papers/w1054.

Broff, Ian. “Bank Run Scene from ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ (1946).” YouTube Video. YouTube, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OTJCI1FNBfA.

Buraschi, Andrea, and Alexei Jiltsov. “Inflation Risk Premia and the Expectations Hypothesis.” Journal of Financial Economics 75 (2), 2005: 429–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.07.003.

Capra, Frank, dir. It’s a Wonderful Life. Film. RKO Radio Pictures, 1946.

“FRB Speech, Bernanke -- on Milton Friedman’s Ninetieth Birthday -- November 8, 2002.” Www.federalreserve.gov, 2002. https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/Speeches/2002/20021108/default.htm.

Freidel, Frank Burt, and Internet Archive. Franklin D. Roosevelt : Launching the New Deal. Internet Archive. Boston : Little, Brown, 1973. https://archive.org/details/franklindrooseve04fran.

Friedman, Milton, and Anna J Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1971. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/36656.

Friedman, Milton, Anna Jacobson Schwartz, and National Bureau of Economic Research. The Great Contraction, 1929-1933. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Griffin, G. Edward. The Creature from Jekyll Island: A Second Look at the Federal Reserve. Internet Archive, 1998. https://archive.org/details/TheCreatureFromJekyllIslandByG.EdwardGriffin.

Kershaw, Ian. Hitler, 1889-1936: Hubris. London: Allen Lane, 2001.

Krugman, Paul. “Who Was Milton Friedman? - the New York Review of Books.” Web.archive.org. April 10, 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080410200144/https://www.nybooks.com/articles/19857.

Lioudis, Nick. “What Is the Difference between Keynesian and Monetarist Economics?” Investopedia. 2019. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/012615/what-difference-between-keynesian-economics-and-monetarist-economics.asp.

Mendoza, Enrique G., and Katherine A. Smith. “Quantitative Implications of a Debt-Deflation Theory of Sudden Stops and Asset Prices.” Journal of International Economics 70, no. 1, September, 2006: 82–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2005.06.016.

Parker, Randall E. Reflections on the Great Depression. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2002.

Romer, Christina D. “What Ended the Great Depression?” The Journal of Economic History 52, no. 4 (1992): 757–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2123226.

Whaples, Robert. “Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on Forty Propositions.” The Journal of Economic History 55, no. 1 (1995): 139–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2123771.